| St Mary's Rotherhithe in September 2015 |

I have added a list of the main sources of information for this post at the end, with my thanks. Unless otherwise stated, all the hyperlinks in this piece link to earlier posts on this blog, which contain more relevant information. Unless otherwise stated, photographs by Andie Byrnes.

|

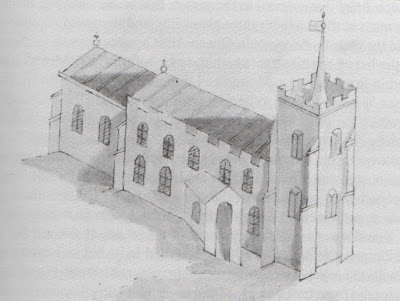

| St Mary's in 1623, by Samuel Palmer. Taken from "The Story of Rotherhithe" by Stephen Humphrey (1997, p.9) |

|

| The memorial to Captain Anthony Wood |

Another contemporary of the old church was Peter Hills, whose legacy founded the charity school for the children of impoverished seamen in the immediate vicinity of St Mary's. Peter Hills died on 26th February 1614, a century before the new St Mary's was built in 1714-15. Fortunately, some of the memorials were taken from the old church and installed in the new one, and the Reverend Beck, writing in 1907, tells how the three portions of a monumental brass dedicated to Peter Hills and embedded into the floor of the old church were taken into the new church and, because they were so badly eroded, were mounted on wood and hung on the wall. The brass includes a portrait of Peter Hills and both wives and the inscription reads:

Here lies buried the body of Peter Hill, Mariner, one of the eldest Brothers and Assistants of the Company of the Trinity, and his two wives; who while hee lived in this place, gave liberally to the poore, and spent bountifully in his house; and after many great troubles, being of the age of 80 yeeres and upward departed this life without issue, upon the 26 February, 1614.

This was made at the charge of Robert Bell.

Though Hills be dead,

Hills' Will and Act survives

His Free-Schoole, and

his Pension for the Poore;

Thought on by him,

Performed by his Heire,

For eight poore Sea-mens

Children, and no more

Photographs

of the Peter Hills brass and the subscription board mentioned above can

be see on the St Mary's Rotherhithe website at http://www.stmaryrotherhithe.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3&Itemid=4.

|

| The Blome Map of 1673 showing the spread of industry and habitation along the Rotherhithe riverside |

A church was vital to the community, its natural core, so plans were made to replace the existing church with a new one. There was great hope in the local community that they would be able to benefit from the Fifty Churches Act, a government-inspired initiative to create more places of worship in London, funded by a tax on coal. The argument outlined in the petition put forward by Rotherhithe residents was persuasive. They attempted to convince the Commission that the community's multiple roles in bringing the coal that was being levied for the building programmes should qualify them for the a new church "being chiefly seamen and Watermen who venture their lives in fetching those coals from Newcastle which pay for the Rebuilding of the Churches in London and the Parts adjacent." However, the bid for this funding was unsuccessful and the community had to pull together to raise the funds for the new church themselves. Funding came from both voluntary contributions and the money that was charged for burials. By 1714 they had raised £4000 (which the National Archives Currency Converter estimates at £306,360.00 in today's money), which was sufficient to purchase a 1000 people capacity church, although financial difficulties were ongoing for many years afterwards and they had to defer plans to build a new tower. The architect John James was appointed and it was he who established the essential ingredients of the architecture that we see today.

|

| St Mary's Rotherhithe in the with its 1747 tower, with ships in the background and a rather untidy churchyard in the foreground. From Beck 1907. |

| One of the more attractive of the gravestones in the churchyard |

The skills of local ship builders were employed in the construction of the interior fittings for the church, and the four internal Ionic columns were made of oak ships' masts, which were then plastered and painted white. Originally the interior contained galleries, box pews and an elaborate three-tiered pulpit. The ceiling was provided with a central barrel vault. Although the carvings have been ascribed to Grinling Gibbons in the past, it is more likely that Joseph Wade may have been responsible for many of the more elaborate wooden carvings in the church, as well as the original reredos. A monument to Joseph Wade is still hanging in the church, reading "King's Carver in his Majesty's yards at Deptford and Woolwich," which was erected on the south wall after his death in 1743. See the British Listed Buildings website for the full technical description of the church.

|

| The interior of St Mary's, showing two of the Ionic pillars that were formed by masts covered with a thin layer of plaster, and mounted on pedestals. |

In 1730 an administrative change led to a strong link between St Mary's Rotherhithe and Clare College, Cambridge. Clare College purchased the advowson of the church, which meant that they now had the right to appoint new rectors to the church. Advowsons usually belonged to Manors, enabling the local Lord of the Manor to influence the rector and the church's role in the parish, but they could be bought and sold, and the benefit to them for Clare was that it allowed them to place their own Anglican clergy beneficially, securing a position for the individual and allowing Clare to influence policy. The first to be appointed was Thomas Curling in 1734.

|

| The Barrow Memorial 1775 |

The organ was created by John Byfield Senior in 1764-5, and although it has been restored some of the original pipes and its original case survives, decorated with musical instruments and trumpet-playing angels. The first organist was Michael Topping who was paid £30.00 per year for his services. Years ago I stumbled across a vinyl L.P. of music recorded on the St Mary's organ and it has a beautiful resonance. A decade later in 1775 another memorial was added. Captain Thomas Barrow dedicated the memorial to his wife Elizabeth who died at the age of 62. His own name was added to the memorial in 1789 when he himself died at the age of 72. The monument is an impressive one, with a coat of arms over the dedication and various funerary symbols surrounding it. The urn is a common funerary device on tombstones and mausoleums. There's a short but interesting article on the Hand Eye Foot Brain blog about the contested origins of that motif.

|

| St Mary's Rotherhithe and Rotherhithe village in 1799 (the Horwood Map, copyright www.motco.com) |

|

| The Prince Lee Boo memorial in St Mary's |

"In the adjacent churchyard lies the body of Prince Lee Boo son of Abba Thulle, Rupack or King of the island Coorooraa, one of the Palew or Palos Islands who departed this life at the house of Henry Wilson in Paradise Row in this parish on the 27th Day of December 1784 aged 20 years. The tablet is erected by the Secretary of State for India in Council to keep alive the memory of the humane treatment shewn by the natives to the crew of the Honourable East India Company's ship "Antelope" which was wrecked of the island of Coorooraa on the 9th of August 1783. the barbarous people showed us no little kindness."

Richard Horwood's 1799 map of Rotherhithe shows the church in its own churchyard, with a long thin burial ground to the south, on the opposite side of the road. To the south and west were dozens of houses with gardens and yards, backing on to each other, as well as a small row backing on to the churchyard to the north. There are few indicators of what some of these houses must have looked like, but the Peter Hills Charity School, which had been a home before it became a school, provides an idea. Slightly later in 1814, William Gaitskell House is another example of the type of residential housing that has been destroyed. Most of Rotherhithe is shown as marshy fields, and a section to the south west of the church, immediately to the south of today's Paradise Street and west of Lower Road is marked as Calanders Gardens, which were apparently the first of the market gardens that slightly enveloped the more cultivable areas of Rotherhithe.

| The 1821 Watch-house |

Memorials continued to be erected in the church. One commemorates Henry Meriton, a senior officer in the Honourable East India Company and participant in the Napoleonic wars who died in 1826. An even more direct connection with the seas is represented by the altar table and two chairs, which were made from timbers that were salvaged from the famous and much-loved ship HMS Temeraire and are still housed in the church today. In 1838 HMS Temeraire was broken up at the nearby Beatson Yard. Temeraire, which had served at Trafalgar, was later made famous by J.M.W. Turner, who painted a somewhat fanciful version of her final trip upriver to the Beatson yard. He had been visiting his mistress in Margate and on his trip home back into London on the Margate steamer saw the ship being towed in. Breaking ships was a lucrative business, due to the ongoing value of the oak that was used to build them, and the various fixtures and fittings that could be resold or recycled. Even old rope could be recycled, a task that had frequently been carried out in workhouses throughout the centuries (hence the phrase "money for old rope"). There is more about Temeraire and the Beatson yard on an earlier post.

|

| Chairs made from timber from HMS Temeraire |

| The memorial to Reverend Edward Blick in the churchyard |

The spire of St Mary's was rebuilt in 1861. The interior has changed considerably since 1714, mainly because of a major

remodelling by Gothic revival architect William Butterfield. Between 1873 and 1889 Butterfield removed the galleries, lowered the pulpit from three tiers to one, added wrought iron rails to enclose the chancel, made space for a choir and added new stained glass windows. He gave the interior a bright face-lift, quite contrary to post-reformation minimalism, and the altar was given a backdrop that is more than a little reminiscent of Pre-Raphaelite ideas in its enthusiasm for gold and vivid colours.

Part of the churchyard was sold to the Thames Steam Ferry Company. Although Reverend Beck mentions it in his book (see below) he doesn't give any idea of when the sale was made. However, a Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Rotherhithe in 1877 shown on the Wellcome Library website mentions it and gives the following account:

Beck says that the land sold to enable its construction was at the northeast corner where the bone house had once been, and that the land was unconsecrated. Given that it was a steam company it has to have been sometime in the 19th century, so I have plonked it in the middle. Beck says that the Thames Steam Ferry Company used the land to widen the road and improve access to the wharf from which the ferry departed. The venture was a failure, as this passage by Beck describes:

In 1913 the tower again caused problems and had to be underpinned. It was paid for by Hubert Car-Gomm in memory of his mother Emily. The Carr-Gomms were the Lords of the Manor of Rotherhithe, a title that dated from Norman times and was related to property ownership and the rights of the incumbent within the local manor. The Carr-Gomms were notable community benefactors. Hubert became the Liberal M.P. for Rotherhithe in 1906, a more modern form of community service. There are lots of photographs of the interior on the St Mary Rotherhithe's website on the Church Interior page.

Part of the churchyard was sold to the Thames Steam Ferry Company. Although Reverend Beck mentions it in his book (see below) he doesn't give any idea of when the sale was made. However, a Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Rotherhithe in 1877 shown on the Wellcome Library website mentions it and gives the following account:

The Thames Steam Ferry adjoining Church Stairs, Rotherhithe, was formally opened by the Lord Mayor, of London, on the 31st day of October, 1877, on which occasion, the vestry caused a suitable address to be prepared and the same was presented to his lordship at the opening ceremony by Mr. Churchwarden Foottit on behalf of the vestry, the vestrymen and officers being in attendance, after which the Lord Mayor in his couch accompanied by the Vestrymen and Officers, was conducted across the Thames upon the company's ferry boat.

Beck says that the land sold to enable its construction was at the northeast corner where the bone house had once been, and that the land was unconsecrated. Given that it was a steam company it has to have been sometime in the 19th century, so I have plonked it in the middle. Beck says that the Thames Steam Ferry Company used the land to widen the road and improve access to the wharf from which the ferry departed. The venture was a failure, as this passage by Beck describes:

The expectations upon which it was founded proved delusive; the fine two ferry-boats with elaborate hydraulic machinery for the passage of vans and cars at all times of the tide failed to tempt the timber-merchants and contractors to shorten by nearly two miles the journey to London Bridge, and, like many other improvements born before their time, the Ferry did but herald the magnificent enterprise of Tower Bridge, with its bascules."

|

| Reverend Edward Josselyn Beck |

In 1867 Reverend Edward Josselyn Beck succeeded Blick and held the position until 1907, another Clare College Fellow. Beck's many contributions to the community included a history of the parish of St Mary's Rotherhithe (published in 1907). Memorials to Serve for a History of the Parish of St Mary, Rotherhithe shows just how important the pedigrees of the incoming rectors were to the status of the church. The photograph to the left was taken from his book. Memorials also records some of the more influential local families of the time, painting a really evocative portrait of how Rotherhithe was put together and what sort of activities were carried out in the area. It also, of course, emphasises the role of the St Mary's in community life. As Rotherhithe developed and expanded throughout the

19th Century the clerics of St Mary's were responsible for extending community support, welfare projects and ensuring children's education in the further reaches of

Rotherhithe as residential areas. Beck himself was responsible for the establishment of several new parish churches but bemoaned the fate of St Mary's at that time in a rather sad section of the book:

We do not forget that the present congregation is far less able to contribute than those who were the resident parishioners in 1867; and the other churches which now quite naturally draw the church people who live in Union Road, in the Lower Road, in Plough Road, and in the streets on the other side of Southwark Park, where there were then market gardens and rope grounds, have left the old mother church almost derelict, surrounded no longer by streets of houses, by wharves, mills, granaries and high buildings, with scarcely an inhabited house near it, like a stranded hulk left high and dry on the shore.

The fate of old city churches is in some respect a sad one. They possess the furniture and fittings and alter plate of a by-gone age, by their congregations have migrated to other homes, and St Mary's Church, Rotherhithe, if not quite so forlorn as St Nicholas', Deptford is yet out of the main stream of life to-day; On week-days it is shaken by the vibrations of an endless procession of timber vans and other heavy traffic; but on Sundays the neighbourhood is quiet that you might think St Marychurch Street and Rotherhithe Street a deserted thoroughfare."

|

| The Old Mortuary of 1895. Photograph copyright Time and Talents http://www.timeandtalents.org.uk/page68/Lettings.html |

With the demise of the ship building industry at the end of the 19th Century, Rotherhithe became a world of docks and dockers, fulfilling a destiny that began in 1699 with the Howland Great Wet Dock. This was a far less differentiated world than that of the ship-builders and their workers, but one that needed more help than it ever had done before. Churches, charities and individual benefactors helped to raise the standards of daily life, but throughout the centuries up until the end of the ship building industries it was clearly a real hotch-potch of diverse livelihoods, lifestyles and standards of living, a mixture of rich and poor.

Other churches and chapels have come and gone, and only a few have remained. Partly through the efforts of St Mary's vicar Reverend Blick in the late 1800s other chapels and churches were established to serve other parts of Rotherhithe as new housing was built. These included All Saints on Lower Road (1839, destroyed in the early 1950s) , St Barnabas on Plough Way (1872, destroyed in the 1960s) , St Paul's Chapel (1850, destroyed 1955) on Ram Alley (later Beatson Street), Trinity Church in Dowtown, on the corner of Salter Road and Rotherhithe Street (1937, destroyed in 1940 and replaced in 1952), and various others. More recently other churches have been added including the Catholic church of St Peter and the Guardian Angels in Paradise Street (1903), St Olav's Norwegian church (1927), built where the entrance to Rotherhithe Tunnel now stands, and the Finnish Church on Albion Street (1958) on Albion Street. However, St Mary's continues to be the oldest and most prestigious of the area's churches.

|

| St Mary's Rotherhithe, September 2015 |

To end on a note of complete trivia, there's a lovely story from 1717 reported in Edward Walford's History of Rotherhithe (1872-78) from the Weekly Packet, dated 21-28th December 1717: "Last week, near the new church at Rotherhithe, a stone coffin of prodigious size was taken out of the ground, and in it the skeleton of a man ten feet long" but, as Walford adds, "this we do not expect our readers to accept as literally true" (p.137). Walford doesn't say why they were removing the coffin from the ground, so that will have to stay a mystery.

Visitors to the area will find that the church is closed during the week, although a side entrance is usually open to allow access to a vestibule which has a glass screen from where it is possible to get a sense of some of the church's interior features. The church is open for Sunday services and Eucharists during the week. It is usually possible to enter the church after the Sunday service without disturbing worshippers after the service when the congregation has departed. St Mary's receives enquiries from people who

are researching their family history. Although the church does not have

copies of

historic Parish Registers of Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, but these can

be found at the Metropolitan Archives in Clerkenwell, London,

and many are available on that website.

|

| The Byfield organ of 1764, also showing part of the lovely ceiling. Photograph by Jim Linwood. sourced from Flickr. |

- St Mary's Rotherhithe Church website http://www.stmaryrotherhithe.org. See the site for many more photographs

- Stephen Humphrey The Story of Rotherhithe. London Borough of Southwark Neighbourhood History No.6 1997

- Reverend E.J. Beck. Memorials to Serve for a History of the Parish of St Mary, Rotherhithe. Cambridge At the University Press 1907. This edition by Bibliobazaar.

- Anon. A Short Account of the Churches, Schools and Charities in the Parish of St Mary Rotherhithe. British Library. Date uncertain - mid to late 1800s.

- Mervyn Blatch. A Guide to London's Churches. Constable and Company Ltd 1978

- Elizabeth Williamson and Nikolaus Pevsner. London Docklands. An Architectural Guide. Penguin Books 1998

- British Listed Buildings website entry for St Mary's Rotherhithe: http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-471286-church-of-st-mary-rotherhithe-greater-lo#.VgxlwyvcrUU

- Edward Walford. History of Rotherhithe. 1872-78

|

| Rotherhithe in 1914, fully developed with docks, houses and foreshore businesses. The location of St Mary Rotherhithe is shown with the red box. |

| The south side of the church |

| St Mary's Rotherhithe in October 2015, with the more modern extension added on its northern side built in the style of the original building. |

| The former extended churchyard as it is today, with the spire of the church visible at top right |

No comments:

Post a Comment